Living Near Trees Has Positive, Measurable Health Impacts

Trees have multiple benefits, but the greatest are for public health, said Geoffrey Donovan, which is why he now focuses 90 percent of his research exploring the link between canopy and human health.

“Trees are far more important than even the most ardent among you can imagine.”

Donovan, a U.S. Forest Service researcher based in Portland, spoke in East Portland on October 28 at a talk co-sponsored by Trees for Life Oregon and Thrive East PDX.

“Trees are far more important than even the most ardent among you can imagine,” he stated, but these benefits are “badly understood.” This is why the public health tie-in to canopy is often ignored by policymakers when making urban forest budget and planning decisions. Yet health care is very expensive, said the economist, and trees are relatively cheap.

Geofffrey Donovan, October 28, 2023.

Donovan highlighted three major findings from his years of research. Shade equity activists can cite these to advocate for Portland City Council to strengthen protections for existing large trees and space in new development to plant new ones. His studies also bolster arguments for the City to assume responsibility for street tree maintenance. Toughening our tree code and getting City leaders to put green infrastructure on equal footing with gray infrastructure is particularly crucial in low-canopy, high-development areas of town such as East Portland. That area is home to many of the city’s most vulnerable residents.

“It’s hard not to wonder why Portland’s trees and space for them are not given much higher priority, if for public health reasons alone, compared to space for gray infrastructure.”

THE FINDINGS

Proximity to trees improves birth outcomes. In research published in 2011, Donovan and his team looked at almost 6,000 live births in Portland, mapping women’s addresses with aerial views of canopy levels near their homes. Because many factors affect birth outcomes, he controlled for race, poverty, pre-natal care, crime, and previous problem births. Women with tree canopy within 50 meters (164 feet) of where they live, he found, are less likely to have underweight babies. Though little of this kind of research was being done in 2011, says Donovan, since then at least 30 other studies—e.g., in California, Spain, Germany, and Canada—have found a similar link. The fact that pregnant women living near trees produce healthier babies than those who don’t is vitally important. Babies disadvantaged at birth by being underweight can have later health and other problems including underachievement and lower earnings. (From TFLO’s perspective, with findings like this, it’s hard not to wonder why Portland’s trees and space for them are not given much higher priority, if for public health reasons alone, compared to space for gray infrastructure.)

Living near trees lowers blood pressure. This and the next visual are courtesy of Geoffrey Donovan.

Tree deaths from emerald ash borer have been associated with a significant increase in human deaths from cardiovascular and lower-respiratory diseases. Donovan found that the more trees that died from the emerald ash borer (EAB) across 15 states, the more people in affected counties died. He and a co-author’s 2013 study analyzed human mortality data from 1990 through 2007, spanning a period before and after EAB’s arrival. His analysis showed that EAB’s spread from Michigan, first recorded in 2002, was associated with an additional 15,000 deaths from cardiovascular disease and an additional 6,000 deaths from lower respiratory disease. Declines in trees due to EAB were also associated with declines in outdoor recreation, which also affects health. (Take note that EAB reached Oregon in 2022. It is expected to threaten and likely decimate Portland’s multitudes of ash trees in the next five to ten years.

“The study found that older trees averted twice as many deaths than younger trees did.”

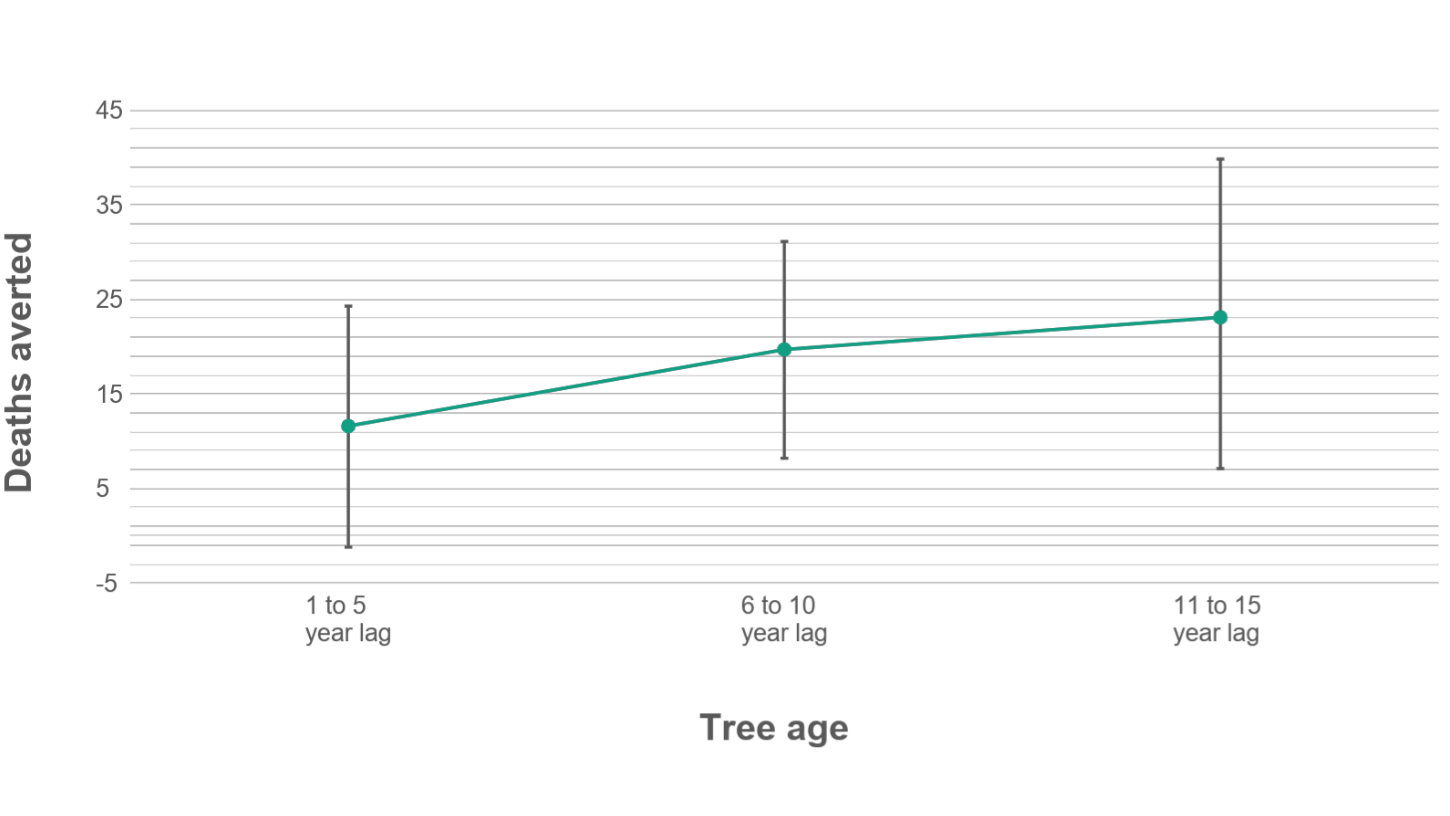

Planting trees and maintaining them over time saves lives and money. Finally, Donovan’s October 28 talk spotlighted a study that he and co-authors published in 2022 based on the treasure-trove of data that Friends of Trees keeps on the 50,000 trees the nonprofit has planted over three decades. Based on the (mostly) street trees planted in the last 15 years, together with Oregon Health Authority-provided census-tract data for the same period, Donovan and his team found that planting 1,638 trees annually was associated with 15.6 percent fewer deaths. One premature death was averted for every 100 trees planted. Because more mature trees provide more canopy, shade, and other health and environmental benefits, it was not surprising that the study found that older trees averted twice as many deaths than younger trees did. Of the 1,638 trees, the 1- to 5-year old trees were associated with 11.6 averted deaths, the 6- to 10-year old trees with 19.7 fewer deaths, and the 11- to 15-year-old trees with more than 23 fewer deaths.

As Friends of Trees-planted trees got bigger and older, they were associated with less mortality. This is why it's so important we actively preserve and maintain large-at-maturity trees.

“Retaining mature trees is at least if not more important than planting new trees.”

“Retaining mature trees is at least if not more important than planting new trees,” said Donovan. So it’s especially important to actively preserve and maintain large-at-maturity trees.

Donovan acknowledges that maintaining trees costs money. But he argued that the benefits outweigh the costs. According to his team’s estimates, planting 140 trees—one in every one of Portland’s 140 census tracts—would annually cost between $2,700 to $13,700 to maintain. But, he said, that cost is tiny compared to the annual savings of $14.2 million, which is the value of the statistical lives that would be saved by these trees. The latter monetary estimate is based on Environment Protection Agency estimates of the value of a statistical life.*

All of Donovan’s findings should be applied to public policies and decisions around urban trees. The strong evidence for trees saving lives suggests, as did a few participants at Donovan’s October talk, that policymakers at all levels should be looking differently at urban forestry budgets. The benefits to Portlanders’ public health from our trees are real and specific, as is evidence that the larger the tree, the more benefits it provides.

At a time when housing pressures are spurring Portland and Oregon leaders to propose quashing canopy and other green infrastructure protections, it’s more important than ever to understand that new housing will not be healthy housing unless it’s designed together with space for new or existing large-form trees. And that investing in maintaining street trees so they reach their full potential to save lives will pay off by the large potential savings in public health dollars.

*As the EPA states, the agency “does not place a dollar value on individual lives. Rather, when conducting a benefit-cost analysis of new environmental policies, the Agency uses estimates of how much people are willing to pay for small reductions in their risks of dying from adverse health conditions that may be caused by environmental pollution.”

To learn more about Donovan’s findings and methodology, watch a 7-minute video and a 39-minute video of similar talks he has given.